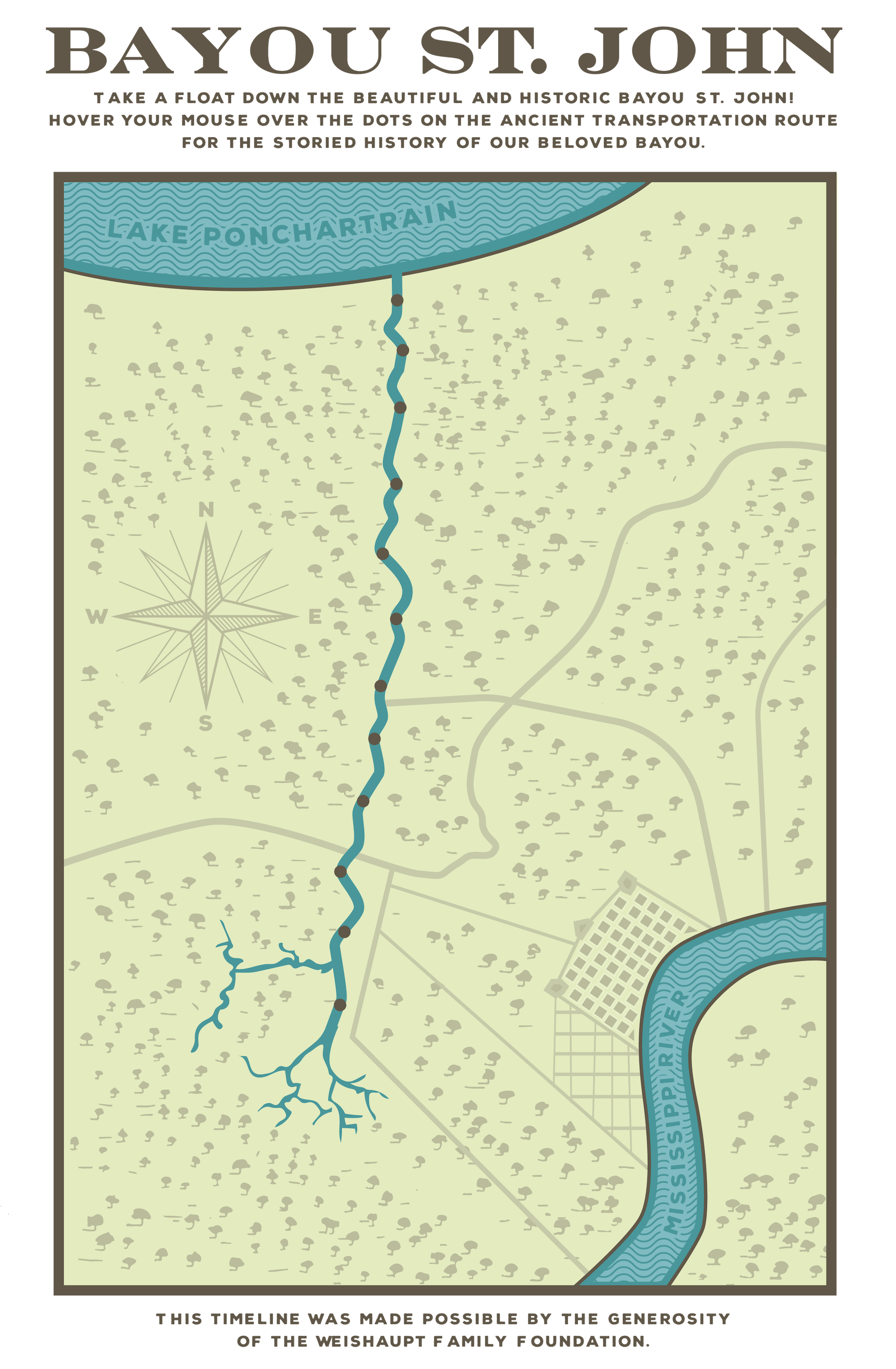

New Orleans, La., Jan. 31, 2013 -- Archaeologists under contract to the Federal Emergency Management Agency survey land near Bayou St. John in New Orleans. The team discovered artifacts related to pre-historic and historic occupations along the bayou. This information was uncovered during a recent archaeological study funded under the HMGP program. Photo by Lillie Long/FEMA

Pre-colonial History: Sometime around 2,000 years ago, Bayou St. John breaks off from the Metairie-Sauvage Distributary, a former channel of the Mississippi River, and begins flowing into Lake Pontchartrain. Indigenous populations, present in what is now known as the Pontchartrain Basin by around 800 B.C., utilize the area for seasonal food gathering and trade, migrating in response to the ever-shifting Mississippi River. The waterways lacing the landscape facilitate efficient transportation, and scholars surmise that Bayou St. John and Metairie Ridge would have been ideal sites for seasonal habitation because they afforded high ground and access to the food-rich lake nearby. In 2013, FEMA archaeologists find indigenous artifacts dating from 300-400 AD at the colloquially-named “Spanish Fort” on the banks of Bayou St. John lakeside of Robert E Lee Boulevard.

1699: Native guides show Iberville a portage route—perhaps including present-day Bayou St. John and Esplanade Ridge—that would allow the French to access the Mississippi River without having to travel up its mouth, a harrowing journey that could take weeks. In 1718, Iberville’s brother Bienville chooses the present-day French Quarter as the site of the future city of New Orleans. Bayou St. John and the swampy overland passage that loosely follows the path of present-day Bayou Road become a critical link for traffic entering and exiting the fledgling settlement via Lake Pontchartrain.

1794: To facilitate drainage and more efficient transportation, Governor Carondelet orders the dredging of a canal from Bayou St. John to the edge of the present-day French Quarter. Enslaved Africans hack through thousands of feet of dense forest and dig a shallow canal along the path of the present-day Lafitte Greenway. The Carondelet Canal, later referred to as the Old Basin, operates as a commercial corridor with varying levels of efficiency and upkeep until the 1930s. Throughout the 19th century, the Bayou St. John/Old Basin corridor boasts both industry and recreation.

1800s – Commercial History: Bayou St. John and the Old Basin Canal continue to operate commercially, although the opening of the New Basin Canal in 1838 and the advent of rail transport present stiff competition. Schooners and luggers haul lumber, shells, charcoal, bricks, sand, firewood, oysters, and produce along the waterway, making use of the bayou’s moveable bridges – including the “Cabrini Bridge,” first located at Esplanade Avenue and relocated to its present location in 1909. The Old Basin Canal, after falling into disuse and disrepair, is filled in by 1938.

1800s – Social and Cultural History: Throughout the 19th century, the bayou offers new social, cultural, and recreational opportunities. Where Lake Pontchartrain meets Bayou St. John, the Spanish Fort summer resort (later morphing into Pontchartrain Beach amusement park) begins hosting patrons in the 1820s, offering victuals and other amusements. The waterway becomes host to popular rowing races; more intimate gatherings such as Voodoo ceremonies occur along and around its swampier sections. During Reconstruction, such ceremonies near the lake attract thousands of spectators seeking to glimpse the famous Marie Laveau

1890s-1907: Aided by engineer Albert Baldwin Wood’s “screw pumps,” a new city-wide drainage system catalyzes residential development along Bayou St. John that will continue throughout the 20th century. City Park expands and receives a major makeover. In 1904, the Missionary Sisters of the Scared Heart move their orphanage for Italian immigrants from “Little Palermo” in the French Quarter to a large lot bordered by Esplanade Avenue and Moss Street; the complex is reborn as Cabrini High School in 1959. The Bayou St. John/Old Basin corridor struggles to remain commercially relevant, as meanwhile the bayou sees an uptick in recreational “pleasure boating.”

1907-1927: The charter granting use of Bayou St. John for commercial purposes expires, and the Carondelet Canal and Navigation Company enters into a seven-year lawsuit with the state over disputed compensation for improvements made to the corridor. During and after the lawsuit, with no formal authority in place to oversee its use and upkeep, the bayou falls into disrepair and becomes an unofficial “houseboat colony,” with privately-owned wharves, boathouses, and floating vessels blanketing its waters at either end. Many houseboats serve as permanent residences for their occupants. The corridor’s character and function hang in the balance.

1920s-1930s: After successfully arguing that Bayou St. John should be used exclusively for recreation, the Bayou St. John Commission, spearheaded by lawyer and businessman Walter Parker, oversees its renovation into a proposed “aquatic park.” By harnessing WPA labor, the commission facilitates the removal of houseboats, boathouses, wharves, and debris; the draining, dredging, straightening, widening, of the waterway; the construction of fixed bridges; and the reinforcement of the banks with revetments, levees, and boat landings. In 1936, Congress declares Bayou St. John (somewhat symbolically) to be a “non-navigable stream,” putting an end to all commerce along its stretch.

1926-1934: The ambitious Lakefront Project dramatically changes the south shore of Lake Pontchartrain from the Orleans/Jefferson Parish line to the Industrial Canal. The lakefront transforms from a marshy stretch of fishing camps to a grassy high ground extending into the lake, reinforced with five miles of seawall. Lake Vista, Lakeshore, Lake Terrance, and Lake Oaks neighborhoods soon follow. Pontchartrain Beach, the amusement park operating near Spanish Fort since 1928, relocates to the end of Elysian Fields Avenue in 1939. Due to racial segregation, New Orleanians of color are relegated to Lincoln Beach in New Orleans East until the 1964 Civil Rights Act takes effect.

1940-1970: Bayou St. John and the lakefront serve as testing areas for the amphibious Higgins boats during World War II. Residential neighborhoods surrounding the bayou, including St. Bernard, Fillmore, and Lake Terrace, continue their rapid development. Nevertheless, Bayou St. John does not enjoy robust recreational use: in 1956, a city ordinance declares it illegal to swim in the bayou, and canoeing on the waterway doesn’t become popular until the 1970s. The bayou suffers stagnation and the spread of unwanted aquatic plants, due in part to the dam-like “waterfall structure” constructed at Robert E Lee Boulevard in 1962.

1970-2005: Founded in 1977, the Faubourg St. John Neighborhood Association becomes one of the most active neighborhood associations in the city. Preservation of the neighborhood’s historical structures becomes a priority. In 1979, the Bayou St. John Improvement Association organizes to fight the Levee Board’s proposed grade-level roadway where the bayou meets Lake Pontchartrain, whose “dam” at Lakeshore Drive would seal off the bayou from the lake. The BSJIA attempts but fails to list Bayou St. John on the National Register of Historic Places, although the waterway is eventually recognized as a historic and scenic river within the State Scenic River System. Due in part to the BSJIA’s efforts, the plan for grade-level roadway is ultimately dropped in 1983.

2005-2020: Hurricane Katrina and subsequent levee breaches devastate New Orleans in 2005. Following the storm, Bayou St. John remains stagnant and debris-ridden for months, until experts craft the BSJ Comprehensive Management Plan in 2006. Alongside other recommendations, the plan proposes the removal of the 1962 “waterfall structure”; in 2014, the structure is removed and an urban wetland is created in its place. In 2015, the Lafitte Greenway opens along the former path of the Old Basin Canal, revitalizing that corridor. Today’s Bayou St. John is once again a recreational hotspot, home to picnickers, boaters, and popular events like Greek Fest, Oktober Fest, and Bayou Boogaloo each year.

Bayou St. John history by Cassie Pryn. Want to learn more? Click HERE to get her book!